|

|

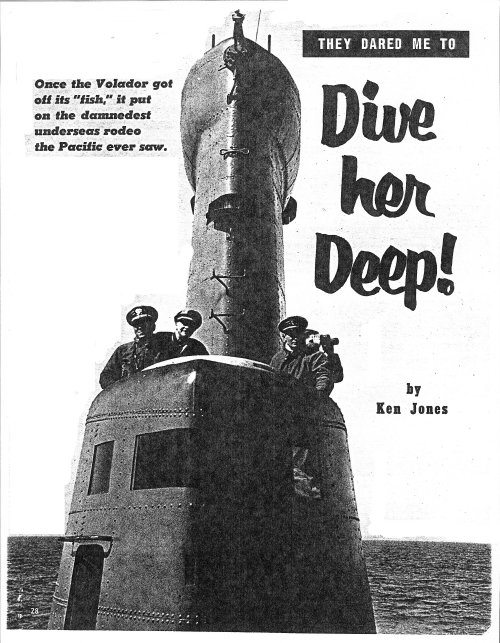

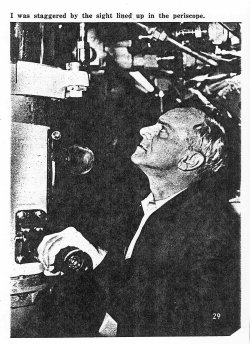

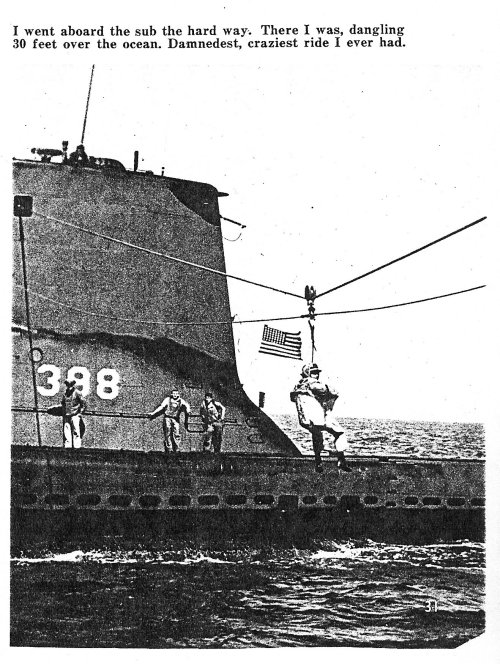

| Dive-Dive-Take her down fast." Commander Eugene A. Hemley, standing at number two periscope of the submarine Volador , rasped out the order- to his diving officer, Lieut. (jg) J. K. Beam. "Full dive on bow and stern planes! Flood negative/" shouted Beam. And then, so far as your curious correspondent Ken Jones is concerned, they lowered the boom! I'm not at all sure that I can report what happened in accurate detail because: (a) An awful lot of things happened mighty fast. (b) The deck started to tilt sharply under my feet as we reached for deep submergence, and I found myself holding on to a stanchion to try to keep upright. (c) The noise of pressure air scared me half to death, and the process was very nearly completed when I looked at the depth gauge and, applying a little rapid arithmetic, figured the force being exerted on our submarine by the water at deep submergence was in the neighborhood of 100,000 tons! If I'd been any less scared I'd probably have shrieked "Get me out of here! " As it was, however, I couldn't even talk, so I just hung on pop-eyed and open mouthed while we were attacked by several of the 11 destroyer screen which we had penetrated to get a spread of torpedoes into the cruiser H elena. I have no doubt that STAG reader George Mattleson, from Cleveland, Ohio, knew what it was all about when he dared me to "Dive her deep," and if I express the pious hope here that all his children turn out to be two-headed idiots, I trust he will understand that it comes straight from the heart. To start with, I can't even swim (not that that would have made a great deal of difference in the circumstances), and to end with; I have a totally miserable record . for even getting into submarines. I can't seem ever to get aboard the right way. The first submarine I ever entered was the U. S. S. Sennet. I chose a moment when she was lying on the bottom off Key West, under 200 feet of water , and the only way to get into her was through the escape hatch after a descent in the Navy's submarine rescue chamber. And if you don't think that's the hard way to board a submarine, just try it some time! I boarded the Volador in equally unconventional fashion. She was cruising in the Pacific Ocean at approximately latitude 32 North, longitude 118 West. I stood with genial Commander John H. (Jake) Bowell in the conning tower of his vessel-the submarine Segundo-and watched the Volador coming up over the horizon. The Segundo was scheduled for other exercises, and if I was going to do any deep diving it would have to be in the Volador. "Well, Captain," I observed with a smirk In the back of my mind if not actually on my face, "I guess .that kills all this deep diving stuff .There he is over there, and here I am over here, and you haven't any small boats or anything like that, and there's a bit of a sea running anyway, and, well, you see how it is. ..,' "Ha! " snorted Captain "Jake" surveying me with re- strained amusement. "We'll put you aboard the Volador." "You will, huh?" My smirk oozed away. "How?" "Breeches buoy," he informed me. And that's exactly how I got aboard the V olador .She came up on our port side, and the two vessels steamed abreast 100 or SO feet from each other at about five knots. The Volador shot a line aboard forward of our conning tower; the crews rigged the breeches buoy tackle conning-tower-to-conning-tower; I stuck my feet down through the holes in the canvas bucket-and the next thing I knew I was off on the damnedest craziest ride I've ever had! There I was, dangling out in space, about 30 feet over the ocean. When the sub- marines pulled apart a little bit, I went up; when they closed slightly, I went down; when they stayed where they belonged, I skidded a few more feet along the rope trolley toward the Volador. Apart from the fact that I had no idea what was sup- posed to happen next-alway a complicating factor- there was a serious aspect to the business. It involved some very adroit ship handling. As the reader mayor may not know, two sizeable vessels running parallel to each other and fairly close, tend to be drawn towards each other. If the watch officers on the two submarines did not counter that tendency to perfection they might have ruined a fine Navy breeches buoy by crushing it between the two vesse]s. Jones, too. If, on the other hand, the vessels were allowed to pull apart too far, their weight could quite easily part the manila line which secured the breeches buoy apparatus be- tween them. In that case the buoy bucket ( or basket, as the Navy calls it) might foul In the propellers or be shredded by being dragged through the water. Jones, too. It should, therefore, surprise no one to learn that in the few minutes it took.me to shuttle from the Segundo to the Volador, I achieved a deep admiration for the officers standing the bridge watch on both vessels. I was welcomed aboard the Volador-a Guppy type submarine by the skipper, and Commander Robert E. lVI. Ward, Division Commander, who led me to the ward room and gave me a quick check-out on the evolutions ahead. Commander Ward talked and I made notes. "We are," the commander told me, "headed for a spot right about here." His pencil came to rest near the center of a 200-square rriile area set apart for submarine evolu- tions and designated as King-King 28 through 34; Item- Item 4 through 8; Item-Item 10 through 14; and Item- Item 4 through 8. "Somewhere in this area there is an 'enemy' task force composed of the cruisers Helena and Toledo, and the destroyers Agerholm, Richard B. Anderson, Bausell, Brown, Dehaven, Hubbard, Mansfield, O'Brien, Rogers, Lyman K. Swenson, and Walke. We know that this task force lay at anchor overnight in Pyramid Cove anchorage, and that it probably was driven to sea early this mornin,g by air attack. We expect it to pass along the westward boundaries of the areas you see marked here on the chart. . Our job will be to find the task force, attempt to penetrate the destroyer screen, and get torpedo hits on the cruisers. It will, of course, be the job of the destroyers to try. to frustrate our attack." "What do we use for ammunition?" I inquired, trying to sound casual, and hoping secretly that the Navy wasn't getting ready to blow itself ot!t of the water. "We'll use torpedoes vvith exercise heads," Commander Ward explained. "They're set to run deep and pass under the ships we shoot at. At the end of the run these sp~cial heads bring the torpedo to the surfacer and we recover it. Each torpedo we fire is accepted as representing the center shot in a spread, which is, of course, what we'd shoot at a cruiser if we had one for a real target." "Very good," I agreed enthusiastically. " And how about the cans-do they drop pickle barrels on us to simulate depth charges?" "No, they drop hand grenades-and if one pops off on top of the conning tower, you'll know it! If they register " N0, they drop hand grenades and if one pops off on top of the conning tower, you '11 know it! If they register a 'good-or-better' hit, we send 'em an air bubble for purposes of record and. .." Commander Ward never finished that sentence, largely because he was talking to an empty seat. All at once the diving klaxon started to blow; hatches began to bang shut, we assumed a sharp diving angle on the bow and I ended up in a stateroom across the passageway. When I got to the control room immediately below the conning tower, I learned that we had picked up the task force by radar at extreme range. Visibility on the surface had been spotty, ranging from 2,000 yards up to 15,000 because of haze. As soon as contact was made, the fire control tracking party started feeding data to two fire control plotting stations, using radar and sonar and visual observations when they became possible. As we closed the range, the skipper had ordered the boat to periscope depth, and I arrived under the conning tower hatch just in time to hear him order, "Up number two periscope! " and a moment later, "Stand by for a bearing! " Swinging the periscope onto the target Captain Hemley called out "Bearing, mark! " On the word "mark:' a buzzer sounded, signifying to all stations watching bearing repeaters that the bearing at that instance was the bearing of the target. It was 007, true. In the control room Lieutenant G. D. Howard bent over his plotting board, translating into visual tracks with swift strokes, dots, and jottings, the confusion of numbers -range, bearing, and time-which now poured in with the rhythm of a metronome. With what seemed incredible swiftness there developed on the paper under his hands a picture which reflected the movements of the task force on the surface, and of the Volador relative to it. I haven't yet quite gotten over the shock of hearing this young officer observe, very casually, "They're on a course of 160 degrees." How did he know? He couldn't see anything- he was way down there in the boat with me-but there it all was on the plot before him. Our first problem was what the Navy people call the "speed solution." Picking one of the destroyers, observations were made every three minutes. After about 10 minutes of this "tracking" there emerged a reliable picture of the course-160 degrees true-and the speed-15 knots -of the task force. It was then up to the skipper to decide how he would attack. The Helena was the first cruiser in line, with the destroyers screening her in a semicircle, the two leading "cans" out in front and about 3,000 yards apart. Captain Hemley decided on a deep dive to take advantage of the thermal gradients in the water, which act to distort the sonar "pings" from the destroyers. Thus he hoped to place himself in front of the task force, and allow the destroyers to pass over him without detecting the Volador. With no strain we slid down to 150 feet, and loafed along there at a speed of three or four knots until the captain's calculations, checked by our own sonar observations, indicated that the lead destroyers had passed over us. The skipper then ordered periscope depth for a quick look around. Our look was a good one, and the captain almost got excited! The lead destroyers were ahead, as he had anticipated, and there, at a range of only about 3,000 yards, was the fat, juicy cruiser Helena! We started maneuvering for a "down the throat" shot. The tension in the boat was electric; it was almost as if every manjack aboard was trying to wish her into position! Then, at last, it came: "Final bearing and shoot! " sang out the skipper from his position at the periscope. "Mark!" The torpedo data computer operator cut in his final bearing and announced "Set! " The assistant TDC operator checked the computer and called "Shoot! " The Executive Officer, Lieutenant James C. Russe11pressed the firing key and our "fish" was away at a range of only 1,300 yards! That's when tile skipper ordered, ..Dive, take her down fast" and the boat went crazy, as far as I was concerned. I started to gag "Is this trip strictly necessary?" but the gag froze in my throat as I watched the big gauge. Down- down-down! It may be old stuff to submariners, but I defy any layman, the first time around, not to phrase the questions in his own mind: Suppose they can't stop this thing? Suppose something gets carried away? We went deep-plenty deep. And then we started to maneuver. The cans were on top of us like hawks, of course, and to borrow the expression of one of the sub- mariners, "They've got us like a mouse under a rug! " We surged through the water at 14 knots-incredible speed when you start computing densities. We slowed, we stopped, we backed down still further; then we went ahead again, twisting and .turning. And then-Bam! Bang! Bam! The hand grenades started raining down around us. For two hours the DD's kept us pinned down, and during that time they landed two grenades close enough for us to send up a shot of air to indicate their good perforn1ance. Each grenade is taken to represent the center of a pattern of depth charges, and on that computation the Volador would have been a mighty unhappy boat to be in during those two hours. We finally came to periscope depth to sweep an empty horizon with the scope, and immediately thereafter we surfaced. In the tense drama of the evolution I found that I had missed some of the values. We had gotten a good hit on the cruiser-pictures taken through our periscope showed her dead in our sights and close aboard. Also we had "scratched one can," although, when we got the shot off at the destroyer I couldn't remember. In retrospect, the only answer I can figure out is: Maybe I was too busy praying to know what was going on! ... |

|

|

|